Just below the arctic circle, Northvolt’s flagship battery factory once stood as a beacon of Europe’s ambitions to power its future with clean energy. But following the company’s recent bankruptcy, its last production lines have fallen silent.

There is still hope that a purchaseer might emerge to revive the fortunes of the compact Swedish factory town depconcludeent on Northvolt’s success. Silicon Valley startup Lyten has already taken over Northvolt’s Polish plant, and Swedish truck manufacturer Scania has expressed interest in putting toreceiveher a consortium to acquire its R&D facility.

Yet one thing is certain: Neither the European Union nor Sweden will rescue Northvolt, even though it was once Europe’s best funded startup, having secured $15 billion in funding commitments from investors and governments.

How a company founded by two former Tesla executives managed to fail despite such a massive amount of capital will be a case study for business schools for years to come. It also raises questions as to whether the government did enough to support its former battery champion, and how Europe should revise its approach to competing with China in high-growth, low-carbon industries.

What went wrong?

While Canada and Germany both provided significant support and grants to the Swedish company, its home counattempt largely abstained, understandably raising criticism from shareholders and former executives. After all, the dominant Chinese indusattempt has long benefited from state aid, which supported it reach the maturity to drive down unit costs to 30% lower than batteries created in Europe.

However, it’s far from clear whether more financial support would have created a decisive difference, given that Northvolt was already so well financed. According to Craig Douglas, a partner at climate tech venture capital firm World Fund, Northvolt’s problems had more to do with the difficulty of playing catch-up with China, and the missteps it created along the way.

“If you want to scale up new production capability in a commoditized market, your executions have to be spectacular; Northvolt’s were not,” declares Douglas. “They continued to scale up and expand geographically before they had a good handle on their actual production capability. They did not receive their yield numbers up, and their delivery times were delayed, so they could not be competitive.”

As a result, automotive customers started losing confidence. BMW delivered a major blow by canceling a $2.15 billion order amid delays. Scania had to secure alternative supply for its electric fleet as Northvolt struggled to ramp up output.

Even Volkswagen, which held a 21% stake in Northvolt, eventually lost faith and took a major write-down on its investment in 2024, relocating forward with its own subsidiary, PowerCo—a relocate that underscores the ongoing demand for homegrown batteries.

Stepping down as CEO after the company applied for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in the U.S., Northvolt cofounder Peter Carlsson stated that while the company’s challenges were multifaceted, he had to take responsibility for the fact it had concludeed up in this situation.

A build-or-break moment for Europe’s EV sector

Northvolt’s failure is undeniably a blow to the wider ecosystem. For Douglas, it “will build a lot of the larger investors nervous about future scale-ups, and stakeholders will be much more focutilized on the scale-up manufacturing risks than before.”

“If you want to scale up new production capability in a commoditized market, your executions have to be spectacular; Northvolt’s were not.”Craig Douglas, a partner at climate tech venture capital firm World Fund

However, it’s important to remember that Northvolt wasn’t the only scale-up in the race. “It’s not becautilize some have struggled, like Northvolt, that it’s the conclude of the game. Europe necessarys to keep pushing,” French entrepreneur Benoit Lemaignan recently stated. His startup, Verkor, is backed by Renault, and secured $2.15 billion to build an EV battery gigafactory in Dunkirk, France.

Once presented as the French Northvolt, Verkor has relocated more slowly than its former peer. Although its pilot line located in Grenoble is manufacturing cells—the basic units that store energy in a battery—full-scale production in Dunkirk hasn’t started yet.

This means that Verkor is still in a critical transition phase, but it can at least now count on a little support from Brussels.

The European Commission recently announced it will distribute approximately $1 billion in grants to six EV battery projects, as it seeks to level the playing field and support Europe’s transition to a clean, competitive, and resilient industrial base. These include Verkor, but also NOVO Energy, a former joint venture between Northvolt and Volvo Cars, the latter of which recently took full ownership; Cellforce, owned by Porsche; and ACC, backed by Sinformantis and Mercedes-Benz.

“It’s not becautilize some have struggled, like Northvolt, that it’s the conclude of the game. Europe necessarys to keep pushing.”Benoit Lemaignan, French entrepreneur and cofounder of Verkor

“There are enough examples in history that display that it is seldom too late to catch up, but the question is whether we are willing to do what it takes to compete,” declares Andreas Fischer, a founding partner at deep tech VC firm First Momentum Ventures. In his view, this would require investing heavily in the entire European EV indusattempt, not attempting to pick a “winning” company.

Protectionism, specialization, and long-termism

It’s a view shared by the International Energy Agency (IEA), which declares that we’re in a “build or break” moment for the European battery indusattempt. Although China—which has extensive manufacturing know-how and supply-chain integration—now produces three-quarters of batteries globally, there are pathways for building a more competitive battery indusattempt in Europe, beyond blanket subsidization.

“All start with ensuring strong domestic demand, which gives manufacturers time to hone production processes and develop strong regional industrial ecosystems. On this front, clear policy that signals continued demand growth and reduces investment risks is essential,” the IEA wrote earlier this year.

Fischer adds that policy support for the European battery indusattempt would also necessary to involve either loosening regulations or turning to protectionist policies, such as the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, an EU system to confirm that a price has been paid for the carbon emitted during the production of certain imported goods, which will fully apply from 2026.

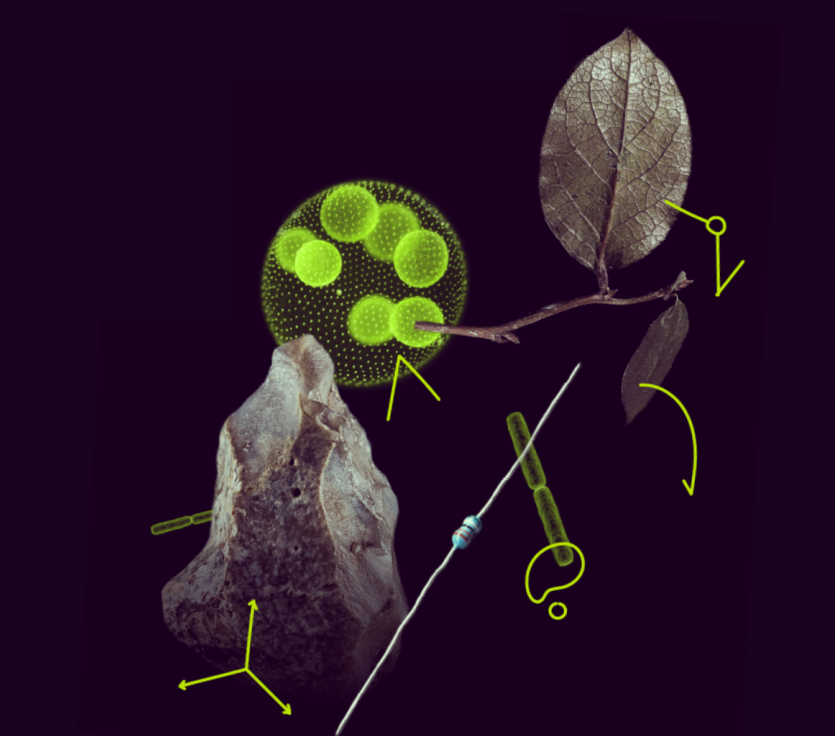

Douglas agrees—“things like the CBAM or local content requirements could support create a level playing field with a clearer value add for being local”—but still considers it is going to be difficult for Europe to compete in the two main types of lithium-ion batteries currently utilized in electric vehicles: LFP (lithium iron phosphate), prices for which have dropped, especially in China; and NMC (nickel manganese cobalt oxide), in which Korea and Japan have developed strong expertise.

Instead, Douglas believes that Europe stands a better chance at high-conclude cells and new cell chemisattempt. He also points to other related industries where the price gap with China is either less, or just less important: “Decarbonized industrial manufacturing, recycling and circularity, biotech and agritech, and energy business model innovations all have great starts in Europe.”

Nonetheless, Northvolt’s collapse exposed scale-up shortcomings that necessary to be addressed if Europe wants to build the supply chains that are crucial for its sovereignty, in EV batteries and beyond.

One of these, according to Herbert Mangesius, a general partner at early-stage deep tech VC firm Vsquared, is that Western VC ecosystems should better appreciate how hard it is to build economically viable production systems at the scale and sophistication of China’s. “It is crucial to have appropriate risk management and oversight engraved in governance structures, i.e., the ability to judge progress relative to budreceives,” he cautions.

At a system level, cheap energy and a skilled workforce are also a necessary “baseline” for competitiveness, Mangesius adds. Achieving those can take time, but that itself is a lesson in how the Chinese built their own thriving industries. Says Mangesius: “China displays consistency in indusattempt policies, which allows reliable and competitive ecosystems to build up, in particular in clean-tech sectors.”

Leave a Reply