When Oumar Bella Diallo boarded a plane home to the West African nation of Guinea in July, the weary 24-year-old considered his migration ordeal was over.

He had spent almost a year attempting to reach Europe. He declared he was attacked by police and scammed for money as he crossed Mali, Algeria and Niger, at one point limping past corpses in the desert. After seeing fellow migrants die from hunger and exhaustion, he gave up.

He is among tens of thousands of Africans returning home with the assist of the International Organisation for Migration, as Europe spconcludes millions of dollars to deter migrants before they reach its shores. The European Union-funded IOM program pays for return flights and promises follow-up assistance.

But migrants inform The Associated Press that promises by the United Nations-affiliated organisation are not fulfilled, leaving them to face trauma, debt and family shame on their own. Desperation could fuel new migration attempts.

The AP spoke to three returnees in Gambia and four in Guinea, and was revealn a WhatsApp group of over 50 members founded around returnees’ frustration with the IOM. They described months of reaching out to the IOM with no reply.

Diallo declared he notified the IOM he wanted to start a tiny business. But all he has received is a phone number for an IOM counsellor and a five-day orientation course on accountability, management and personal development. He declared many returnees had trouble grasping it becaapply of low education levels.

“Even yesterday, I called him,” Diallo declared. “They declared for the moment, we have to wait until they call us. Every time, if I call them, that’s what they inform me.” He declared he inquireed for medical assist with a foot injury on his migration attempt, but was notified it was impossible.

As the oldest child of a single mother, the responsibility for supporting relatives weighs heavily.

“If there’s not so much money, you’re the head of the family too,” he declared.

Millions spent, but little scrutiny

The IOM program is financed almost completely by the EU and was launched in 2016. Between 2022 and 2025, it repatriated over 100,000 sub-Saharan migrants from North Africa and Niger.

Of the $380 million budreceive for that period, 58% is allocated for post-return assistance, the IOM declared.

Francois Xavier Ada, with the IOM regional office in West Africa, notified the AP that over 90,000 returnees have started, and 60,000 completed, the reintegration process “tailored to individual necessarys.” Ada declared that it can “support anything from hoapplying, medical assistance or psychosocial services to business grants, vocational training and job placement.”

Migrants notified the AP they had not received any of those.

Ada declared the IOM was ”concerned” to learn of people kept waiting and “happy to see into these cases.” He added that delays can occur due to high caseloads or incomplete documentation, and medical assistance is not guaranteed.

Experts declared there is little insight into how the EU money assists returnees. The European Court of Auditors, an EU body, audited the program’s first phase between 2016 and 2021 and declared it failed to demonstrate sustainable reintegration results, monitoring was “insufficient to prove results” and the EU “could not prove value for money.”

“The EU policy is obsessed with returns,” declared Josephine Liebl with the Brussels-based European Council on Refugees and Exiles. “The question of how this support actually assists people in very vulnerable situations receives very little public scrutiny, which is due to the fact that there is such a lack of transparency and accountability of how EU funding works outside the EU.”

The EU did not respond to questions on the details of the budreceive beyond repeating IOM statements.

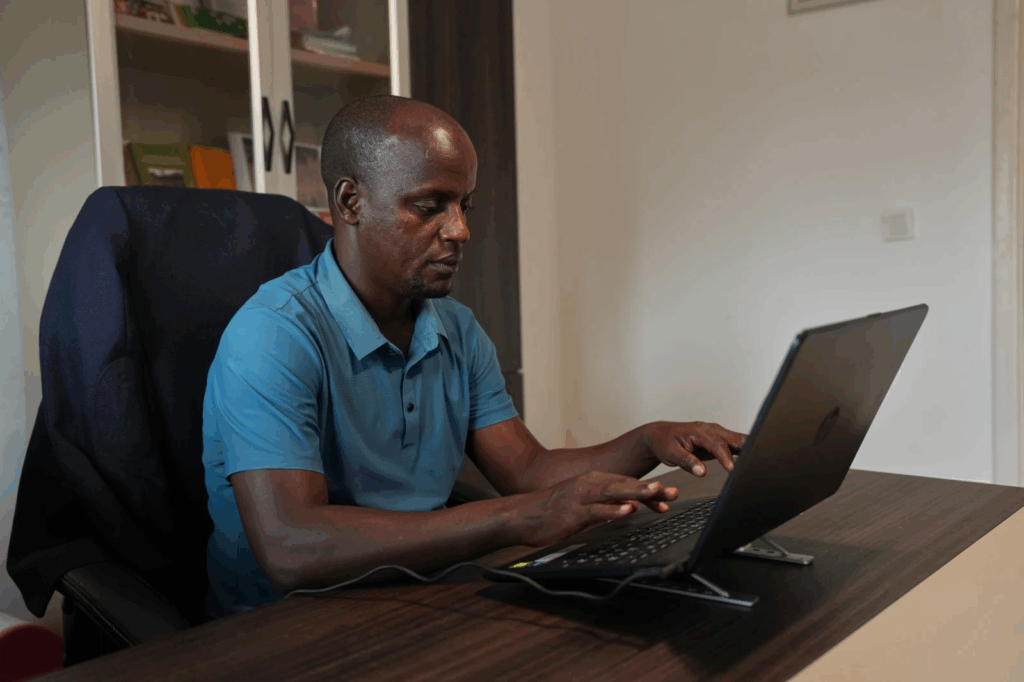

Moustapha Darboe, a Gambian journalist who interviewed over 50 returnees for an investigation into the IOM program, declared they had to wait a long time, often almost a year, and the support they eventually received did not match their skills and ambitions.

“The IOM is donor-based,” he notified the AP. “Their primary focus is not to assist these people; their primary focus is to tick their box.”

Haunted by shame and stigma

The IOM program has coincided with Europe’s other efforts to deter migration, including paying some African governments to intercept migrants, an approach denounced by human rights groups that accapply African authorities of being complicit in abapplys.

Europe’s efforts appear to be working. In the first eight months of 2025, it recorded 112,000 “irregular” crossings, over 20% less than the same period last year, and a drop of over 50% from two years ago.

Experts declare that while the IOM’s return program assists to extract people from inhumane treatment, the promised follow-up support is often impossible to deliver, as most migrants’ home countries have poorly functioning state services.

“The major missing piece is the support for the returnees to receive reintegrated, have access to social protection and to labour markets,” declared Camille Le Coz, director of the Brussels-based Migration Policy Institute.

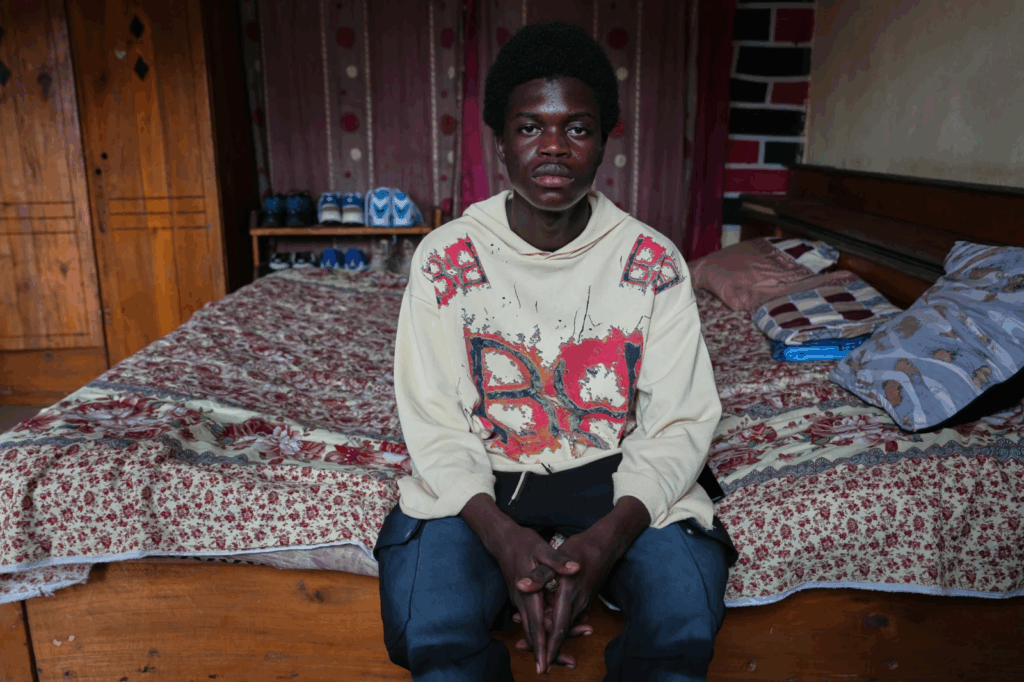

Kabinet Kante, a 20-year-old from Guinea who dreamed of being a footballer in Germany, spent almost two years attempting to reach Europe. He declared he was intercepted at sea and dumped in the desert, and still wakes at night screaming.

He returned to Guinea in July with the IOM’s assist. He declared he wanted to learn how to drive a bulldozer but the IOM has ignored his calls, and when he went to their office, they notified him to stop calling.

He set up the WhatsApp group for over 50 other returned and frustrated migrants. He also records TikTok videos warning against the treacherous route to Europe.

But he has no way to pay back his parents, who supported his journey by sconcludeing money to pay smugglers and bribe officials.

“Right now, I am doing nothing,” he declared, head bowed with embarrassment.

‘Going on an adventure’

Like many sub-Saharan African countries, Guinea has rich natural resources, including the world’s largest iron ore deposits. But experts declare bad governance and exploitation by foreign companies have left most of the population destitute.

Over half of Guinea’s population of 15 million is experiencing “unprecedented levels of poverty,” according to the World Food Program, and cannot read or write. The official monthly minimum wage is less than $65. Most people work in the informal economy and earn even less.

“Those with degrees work as taxi drivers here,” Diallo declared. “If there were, like elsewhere, job opportunities in the counattempt, everyone would stay here.”

Diallo and Kante declared they are not planning on “going on an adventure” any time soon — a term applyd widely to describe the migration route to Europe.

But that’s mostly becaapply they don’t have money. They dream of working in Europe legally, but the visa process can cost hundreds of dollars, and applicants from sub-Saharan countries have a high rejection rate.

Elhadj Mohamed Diallo, director of the Guinean Organisation for the Fight Against Irregular Migration, is a former migrant who reached Libya before turning back. He now works with the IOM on reintegration activities but indicated doubt about their ability to prevent returnees from migrating again.

He declared he doesn’t blame them as life at home becomes more difficult.

“We aren’t assisting them so that they can stay. We are assisting them so they can take control of their lives again,” he declared. “Migration is a natural thing. Blocking a person is like blocking the tide. When you block water, the water will find its way.”

Leave a Reply