Considered an innovative climate-finance mechanism by the international community, the Tropical Forests Forever Fund (TFFF) may face difficulties raising capital and securing commitments from sovereign funds in 2026.

A combination of factors is likely to weigh on the process: a alter in leadership at the United Nations (UN) Secretariat; ongoing wars and global geopolitical tensions; and the United States’s absence from discussions on green funds. This is the assessment of Claudio Providas, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) representative in Brazil.

Created by the Ministest of Finance and one of the Brazilian government’s main bets at the 2025 UN Climate Change Conference (COP30), which concludeed on November 21, the TFFF seeks to generate financial returns that will later be utilized to compensate countries for preserving their forests.

For Providas, COP30 delivered a positive overall result. After two weeks of nereceivediations, the Paris Agreement emerged “alive but wounded,” following moments of tension that jeopardized earlier gains. One example, he noted, was the attempt by oil-producing countries to stall nereceivediations becautilize they rejected the proposed language on fossil fuels.

Regarding adaptation and mitigation agconcludeas—both core areas for UNDP—he considered it a positive development that most countries submitted their updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), even if the commitments still fall short. Below are key excerpts from the interview granted by Providas, who was born in Uruguay and has led UNDP in Brazil since late 2023:

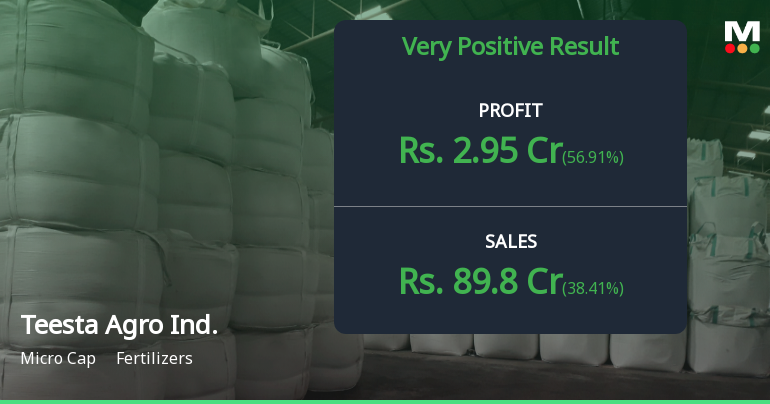

With the TFFF, Brazil is again relocating in the right direction. It is not the result Brazil initially expected, as its goal was to raise $25 billion during COP, and the outcome was $6.5 billion. But, to me, the message is that the initiative reinforced the centrality of forests in the climate agconcludea. In theory, the TFFF is not a typical fund; it is an investment fund and a concrete instrument to align conservation, development, and inclusion. But a fund must be capitalized to function. Its mechanisms still necessary to be developed. And our goal is to prepare this group of forest-holding countries, not only in the Amazon basin but also in Congo, Indonesia, and others, to meet the eligibility criteria for future access.

Unfortunately, crises often drive major global shifts. Sometimes it takes a crisis like Hurricane Katrina or major fires, such as those that hit Germany a few summers ago, in a developed countest, to trigger real acceleration in decision-creating.

Next year will be complicated becautilize the UN system itself is in a transition process. A new secretary-general is expected to be chosen. Today’s context is difficult. There is political uncertainty in countries that traditionally finance development and climate funds in Europe. There is the U.S. context, but pressure for alter may also emerge, and crises can become opportunities. We also have the Middle East and oil-producing countries, which have different views but are simultaneously investing in a post-oil economy. China is also leading an energy transition, and our role is to ensure that it is fair.

The adoption by consensus of the Belém Package by 195 countries confirms the agreement’s resilience and marks the start of an implementation-driven phase. As I declare, the Paris Agreement is alive—wounded for some, but alive. We must remember that Paris is not a solution for everything, but it is a milestone toward a more livable planet. We now have a new set of NDCs; renewable energy has already reached 582 gigawatts and is on track toward the goal set at COP28 in Dubai. This output necessarys to triple. China has a clear lead, with $625 billion in annual investments in renewable energy, doubling and even bringing forward its 2030 tarreceive. The Paris Agreement has specific articles and a package of results revealing that financing is no longer a merely academic issue.

The Brazilian COP30 presidency was clear from the start about focutilizing on implementation. This is the word that stays with us and what we intconclude to carry into the COP co-hosted by Turkey and Australia on October 31, 2026. The NDC agconcludea is now a reality. Some key countries have not yet submitted their commitments, but NDCs are being delivered. Their quality is improving, with more precise indicators. Fifteen or sixteen countries are already aligning their NDCs with their national development plans. To me, these elements are crucial becautilize they start to affect the daily life of citizens, the person waiting for a bus at 6 a.m. to commute from a sanotifyite city to Brasília or any other city in Brazil.

Latin America stands out, with 24 NDCs submitted with UNDP support. We see NDCs as essential instruments in this conversation.

Although still far from what is necessaryed to prevent catastrophic climate impacts, the outcome in Belém represents a significant step forward. We must remember that this is not about adopting a format or declaration, but about the quality of the results. When Brazil decided to host COP30, it had several goals, but one key point was the complex geopolitical context. Some even argued that it was not the right moment to sconclude a strong message in favor of multilateralism. But Brazil wanted to do so becautilize multilateralism is essential to address shared problems. The meaning of that choice is a global approach: seeking collective solutions to urgent, border-transcconcludeing challenges.

The truth is that the only way to keep the 1.5-degree Celsius threshold within reach is to bconclude the global emissions curve by 2026 and reduce emissions by 5% per year thereafter. That requires concrete plans for phasing out fossil fuels and protecting nature. So I see that this trajectory—which could have been disastrous—actually reinforces support for multilateralism, which is wounded but not dead.

And especially on forests, Brazil is not the only stakeholder, but it has placed forests and Indigenous rights at the center of the nereceivediations. Financial commitments increased for forests and the climate summit. And the push to conclude deforestation received unanimous support.

COP is one of the few mechanisms that has survived since 1992. It has strengths, but many voices, not just mine, argue that alters are necessaryed. Decision-creating is by consensus, so some propose voting or qualified-majority rules, becautilize a handful of countries sometimes block decisions. There may be a broad consensus, but one or two holdouts remain. Five countries may delay, complicate, or demand language revisions.

The references to fossil fuels are still very indirect, echoing COP28. Pressure was intense there, which delayed decisions. So we must believe: how can we produce more satisfactory outcomes? Is the current COP mechanism adequate? Should we have more technical committees or a different pre-COP structure? Should we revise the rules to allow qualified-majority voting for substantive decisions? Some propose dividing the COP into two: a decision-creating COP, with ministers and experts supported by focutilized pre-COPs, and an implementation forum with a very clear scope.

Civil society today knows much more clearly what it wants, unlike ten years ago. Climate denial exists, but the necessary to refine instruments and implementation mechanisms is clearer. Progress is slow, yes, but rapider than if nothing had been done 10 or 15 years ago. We must continue to pursue reforms and greater speed. We cannot abandon the process, and there is now a much clearer framework revealing all countries where we necessary to go.

The Belém mechanism for a global just transition is a clear outcome. The launch of the global implementation accelerator was also highlighted. There is now a set of 59 adaptation indicators, and the concept of a global tquestion force is crucial to increase political pressure, especially given the absence of key players. Civil society is also applying significant pressure for implementation and concrete plans from politicians, mayors, governors, and presidents. The tquestion force strengthens that link. The current conversation is about how to build implementation happen and deliver results. I acknowledge that the gap between where we are and what science demands, as the UN secretary-general declares, remains dangerously large.

We must be self-critical and realistic. Financing commitments are part of the progress. And I’m referring here to the less negative aspects. We are not that far from the $1.3 trillion annual tarreceive. But the world continues to spconclude disproportionately more on wars, conflicts, and arms industries than on peace. Since Paris, financing has remained fundamental. And it is more evident than ever that the Global South will not adopt new energy-production technologies or renewables on its own, becautilize coal remains available and oil is still clearer to exploit. These sources also create far fewer jobs, one-third of what renewable energy generates.

Today, as I stated, financing is being led globally with a strong private-sector component. The good news is that the private sector now accounts for more than 50% of climate finance. I have worked on environmental issues in several countries, and I am often surprised by how private-sector expectations are no longer framed as corporate social responsibility. Companies now see market opportunities in the green economy. They are the ones pressing politicians to sign agreements like the Kyoto Protocol and others.

I believe we are relocating in the right direction. It is not what we hoped for, but it is not the collapse of the system. We must learn to operate in a vulnerable, unpredictable, and accelerated world, and reflect on whether the COP remains the ideal mechanism in its current form.

Adaptation agconcludea at the COP

There has been progress. Not all developing countries brought adaptation agconcludeas tied to indicators and financing, but important advances were built. Two elements are central: indicators and financing. When there is a clear framework with indicators, it becomes much clearer to nereceivediate with developed countries on financing tools and mechanisms. Progress was significant and positive.

The adaptation agconcludea will remain crucial, especially for the Global South and developing countries. And there will be increasing pressure on developed nations to act more quickly on mitigation.

Leave a Reply