EU-funded researchers are scaling up sustainable production of microalgae-based proteins, lipids, pigments and carbohydrates that could transform food, animal feed and fragrance industries worldwide.

By Kaja Šeruga

On the outskirts of Lisbon, an abandoned industrial site has been given a new lease of life as a state-of-the-art biorefinery. It is scaling up the production of microalgae – a new source of nutrition.

These single-celled organisms can produce compounds such as proteins, lipids and carbohydrates with very little water and no required for arable land – all crucial elements in the quest to improve food security.

But there is a catch. It remains challenging to grow and process microalgae at a scale and cost that can compete with common nutritional products like palm oil or soybeans.

Changing food production

The Lisbon site, part of an EU-funded research collaboration called MULTI-STR3AM, may have offered a way forward. The cooperation brought toreceiveher a multinational team of researchers and industest experts to tackle this challenge.

“You can cultivate microalgae in old industrial sites or other areas that are not suitable for agricultural apply,” declared Mariana Doria, head of business and market analysis at Portuguese biotechnology company A4F – Algae for Future. She coordinated the international collaboration, which ran from 2020 to April 2025.

Agriculture currently applys almost 40% of land in the EU and a quarter of its water. Separating food production from land is therefore a crucial step towards improving food security and a more sustainable food industest.

MULTI-STR3AM was funded by the Circular Bio-based Europe Joint Undertaking. This public-private partnership between the EU and the Bio-based Industries Consortium supports research that assists the transition towards a competitive, sustainable, and low-carbon economy in Europe.

“The world is altering, agriculture is altering,” declared Rebecca van der Westen, senior product technologist at Flora Food Group, a Dutch branded food company active in over 100 countries worldwide.

“So, how do we sustain ourselves in a healthy way? Microalgae are one of the answers.”

When the opportunity came up to collaborate with international researchers, van der Westen seized it. “I love working in niche areas – that’s where you find the gold,” she declared.

Algae alchemy

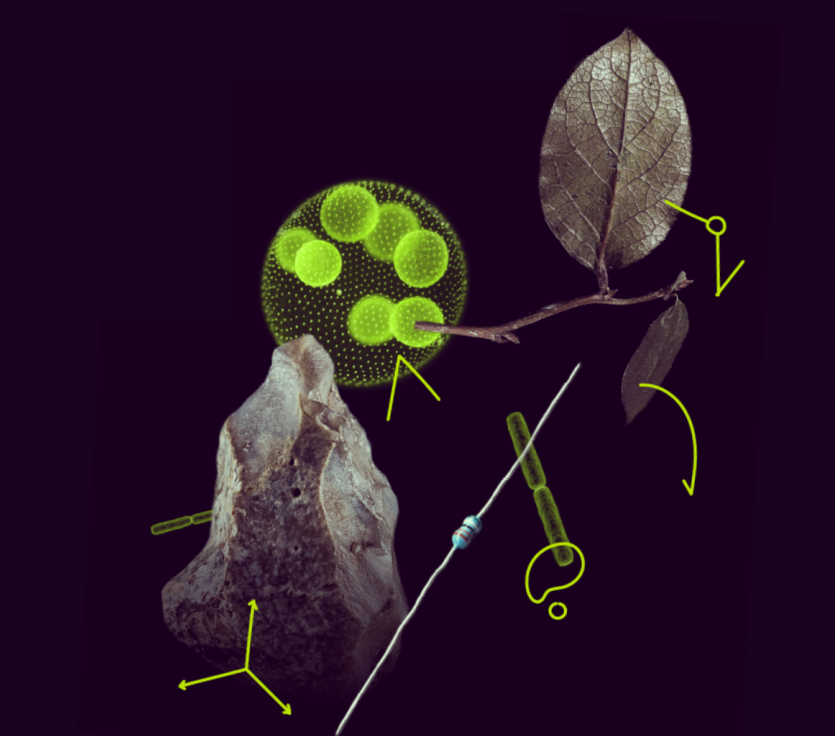

To grow, microalgae required water, CO2, and essential nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus. Through their metabolic processes, they turn these inorganic nutrients into glucose and other organic molecules.

Most of the time, this process happens through photosynthesis, which requires sunlight. However, some microalgae can grow in the dark by feeding on organic nutrients such as glucose, a process known as heterotrophic growth.

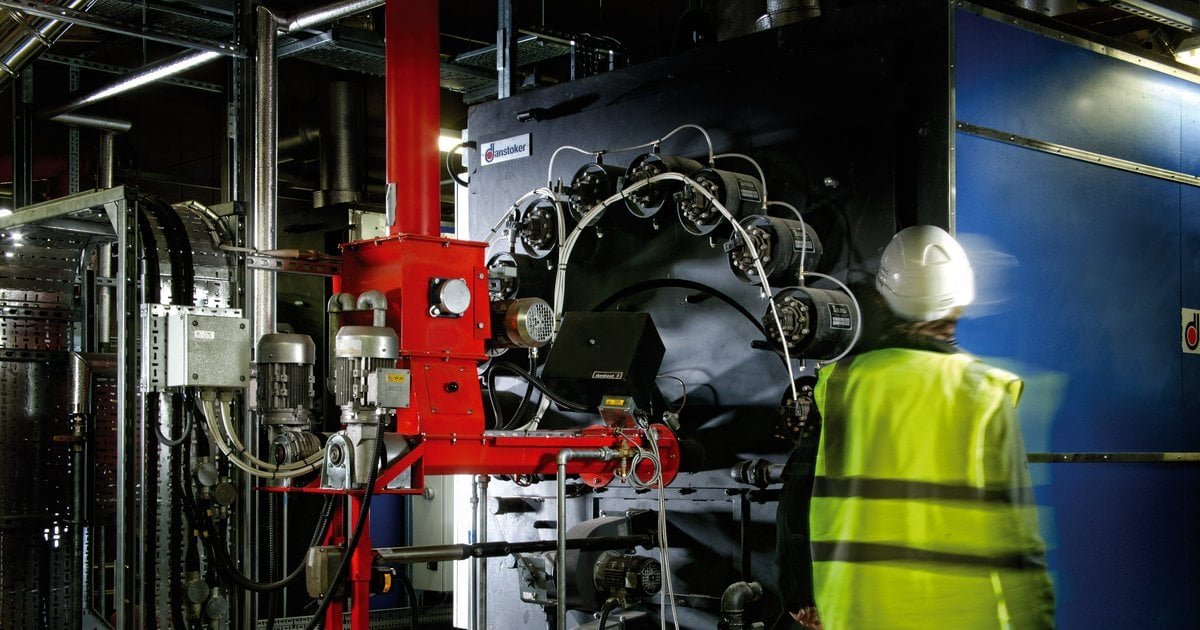

In MULTI-STR3AM, microalgae are cultivated in photobioreactors or fermentation tanks. Once they have grown sufficiently, their biomass is harvested and transferred for processing at the Lisbon biorefinery.

The microalgae cells are broken open, and their valuable components – proteins, lipids, pigments and carbohydrates – are separated and refined into usable ingredients.

The facility processes around 10 tonnes of biomass per year and is designed to handle a wide range of microalgae strains.

To increase sustainability, waste CO2 from natural gas combustion is fed back into the system as a resource for microalgae. Liquid waste from nearby industries serves as the culture medium, and water is recirculated after biomass is harvested.

Finally, the processed ingredients are supplied to various industries for apply in consumer products.

Multipurpose product

As the researchers overcame technical barriers to cultivating and processing microalgae at scale, their advances opened the door to a diverse range of potential products.

Over the course of the research, more than 40 samples of microalgae-derived ingredients were created for industest partners in the food, animal feed and fragrance sectors.

Working across countries and sectors was crucial to ensuring that the ingredients could eventually be applyd in consumer-ready products, declared van der Westen. “Cross-collaboration is fundamental becaapply everybody has their strengths.”

After considering technical and financial viability, as well as market potential, the research team eventually narrowed their focus down to three core ingredients: beta-carotene-rich oils applyd as food colourants and antioxidants in spreads and cheese, protein-rich additives for animal feed, and protein-based capsules that protect and gradually release fragrance ingredients.

Scaling up

Van der Westen is keen to dispel the common misconception that microalgae-based ingredients taste like algae. The ingredients are not simply ground-up biomass, she declared. In the biorefinery, the cells are opened and their molecular structures separated.

“If you view at the basic structure of a fatty acid chain or a few amino acids forming a protein, they exist in microalgae and don’t have a taste or smell,” declared van der Westen. “They contain the same fats as olive oil and similar proteins to poultest, fish and beef.”

Integrating multiple technologies, microalgae strains and production methods into one centralised biorefinery was a major step towards scaling up. But developing a deeper understanding of each microalgae strain was equally important.

“Some microalgae are better known and clearer to scale up, while for others we still required to learn how,” declared Doria.

Part of this work involves determining the ideal growth conditions for each strain, including temperature and nutrient levels, so they can grow quicker and yield the most nutritional value.

“When shifting from the controlled environment of the lab to larger scales, we required to understand which parameters are most sensitive,” declared Doria.

This knowledge also assists scientists steer production towards specific outputs. “We can adjust conditions to create them produce more of one ingredient or another, depconcludeing on our goals,” she declared.

From lab to market

Currently, these new ingredients are undergoing rigorous testing and tasting before they can reach supermarket shelves, declared van der Westen. While this work is still in the early stages, she is confident that microalgal ingredients will eventually become mainstream.

“Microalgae are definitely going to be part of our food in the future. That’s just a question of time,” she declared. For van der Westen and her research team, their work is part of a mission to reimagine how we produce food sustainably and develop a concrete blueprint for the future.

“If you want to sustain a happy planet, you required to do this type of research,” she declared. “It is fundamental for the future.”

Research in this article was funded by the EU’s Horizon Programme. The views of the interviewees don’t necessarily reflect those of the European Commission.

This article was originally published in Horizon the EU Research and Innovation Magazine.

More info

Related

Discover more from Horizon Magazine Blog

Subscribe to receive the latest posts sent to your email.

Leave a Reply