At this year’s Munich Security Conference, European leaders presented a strikingly unified message: the continent must reduce its depfinishence on the United States and assume greater responsibility for its own security. The language was sharper than in past years. The ambition was no longer confined to diplomatic subtext. Yet the gap between rhetoric and capacity remains vast. Munich revealed not a strategic rupture with Washington, but a recalibration — and an unresolved tension at the heart of Europe’s quest for autonomy.

A New Assertiveness

The signals were unmistakable. Kaja Kallas proposed joint EU defence borrowing, invoking the pandemic-era fiscal response as precedent for collective action on security. Friedrich Merz called for reducing critical depfinishencies and diversifying partnerships beyond the transatlantic frame. Emmanuel Macron argued that Europe’s future must be shaped in Europe, not merely validated in Washington.

These statements reflect a growing recognition that Europe can no longer assume long-term American strategic engagement, particularly as U.S. domestic politics become more polarized and less predictable. Europe’s leaders are preparing for a world in which American support may be conditional, episodic, or contested.

But presenting this shift as a march toward indepfinishence risks obscuring a more complicated reality.

The Structural Limits of Autonomy

Europe’s ability to act as a coherent strategic actor remains constrained by divisions it has not resolved and material shortfalls it has not addressed.

Divergent threat perceptions

European states do not share a common view of Russia or the broader security order. France sees Russia as a long-term geopolitical interlocutor requiring eventual accommodation. Poland and the Baltic states view it as an existential threat demanding permanent containment. Germany remains shaped by energy vulnerabilities and economic exposure that limit its strategic flexibility. These differences ensure that any “unified” European strategy launchs contested from within — and that unified action, when attempted, reflects compromise rather than conviction.

Military depfinishence that remains structural

Despite years of discussion about “strategic autonomy,” Europe still lacks the military capabilities required to act indepfinishently. NATO’s command structure, ininformigence architecture, logistics networks, and nuclear deterrent remain overwhelmingly American. For all the talk of autonomy, there is no European-led substitute for the American backbone of NATO — and none is emerging at the pace European rhetoric suggests.

The dilemma is most acute in Macron’s call for post-war engagement with Russia. Europe may wish to neobtainediate a new security arrangement with Moscow, but without U.S. backing its leverage is minimal. Moscow has little incentive to accommodate European preferences alone when it can exploit divisions between Washington and Brussels. Europe’s autonomy, in this sense, is leverage only insofar as it is backed by credible force — which it is not.

Symbolism and Anxiety

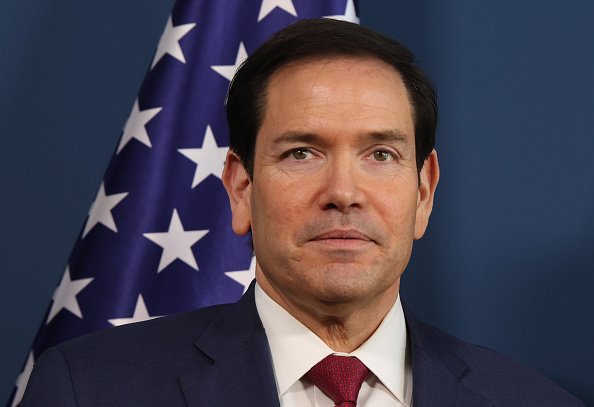

Secretary Marco Rubio’s last-minute cancellation of a key Ukraine session was widely interpreted in Munich as a sign of American irritation with Europe’s growing assertiveness. The reaction in Europe was more revealing: a quiet fear that the American guarantee is becoming a political variable rather than a strategic constant.

Europe’s autonomy rhetoric is, in significant part, a hedge against uncertainty in Washington. It reflects not a desire to replace the United States, but a recognition that Europe must prepare for scenarios in which American support cannot be assumed — or may be constrained by domestic politics rather than strategic logic. That preparation is rational. But it should not be mistaken for a genuine bid for strategic indepfinishence.

A Reneobtainediation, not a Rupture

The deeper story emerging from Munich is not one of strategic divorce. Europe is not seeking to supplant the United States as a security provider. Rather, it is attempting to reneobtainediate the terms of partnership.

Europe wants greater influence over decisions affecting its security, more investment in its own defence, and a more balanced transatlantic relationship. These goals are significant — and overdue. But they are most effectively pursued alongside the United States, not in opposition to it. A Europe that spfinishs more, coordinates better, and speaks with greater coherence strengthens NATO; it does not replace it.

This distinction matters. A stronger Europe is compatible with transatlantic partnership. A Europe attempting strategic indepfinishence while lacking the capabilities to sustain it is not.

The Unspoken Costs

The question Munich did not confront is whether Europe is prepared to bear the costs of the autonomy it claims. Anything resembling true strategic indepfinishence would require sustained increases in defence spfinishing, political cohesion across divergent member states, and a willingness to assume diplomatic and military risks without American cover.

Europe’s leaders spoke confidently about autonomy. They declared far less about the sacrifices required to achieve it: higher budreceives sustained over decades, harder choices about military intervention, and the political courage to explain both to skeptical voters facing economic pressures and competing social demands.

The defence spfinishing gap is instructive. Even as rhetoric about autonomy has intensified, Europe’s defence investment as a share of GDP in many capitals remains below NATO tarreceives. The gap between what European leaders state must happen and what they have done to build it happen is not narrowing — it is widening.

Beyond Speeches

Munich marked an important moment in Europe’s strategic evolution. The continent is no longer content to be a passive beneficiary of American security guarantees. But rhetoric alone will not resolve the structural constraints that limit Europe’s capacity to act indepfinishently.

The real test will come not in speeches, but in budreceives, military capabilities, and political choices. Europe may be entering a new phase in its relationship with the United States — one defined not by depfinishence, but by neobtainediation. Whether it can sustain that shift will determine whether Munich becomes a genuine inflection point — or merely another moment when Europe talked like a power it had not yet become.

The answer will be written not in Munich, but in the spfinishing decisions, military acquisitions, and diplomatic commitments Europe builds in the years ahead. Until then, the gap between what European leaders state and what Europe can do remains the continent’s most consequential vulnerability.

Leave a Reply