Artificial innotifyigence is no longer a futuristic abstraction. It is here, quietly reorganizing economies, governance systems, and the meaning of human relevance. From predictive algorithms in healthcare to generative models in journalism, AI’s reach is expanding at a pace that unsettles policycreaters and excites innovators. Yet beneath the promise lies a sobering reality: monopolization by Big Tech, uneven accessibility across nations, and deep anxiety about the future of work. The global conversation on AI governance often revolves around ideals such as trustworthiness and human‑centered design. These are necessary, but they risk becoming hollow if governance fails to address the lived realities of workers, compact businesses, and under-resourced nations. Democratization, accessibility, and workforce adaptation are not optional. Without them, AI risks becoming a tool of disparity rather than progress.

The democratization dilemma

AI’s democratization challenge is stark. A handful of corporations dominate advanced models, infrastructure, and distribution, setting the terms for who participates and who is left out. That power concentration translates into high costs, proprietary barriers, and depfinishence on closed ecosystems. For nations and firms without deep capital or sovereign compute, access is restricted by privilege rather than required. In India’s case, the gap is not only affordability but also capacity. The IndiaAI Mission has signalled ambition, yet the counattempt still faces missing pieces in talent, data, and research depth. As the Carnegie Endowment argues, nurturing top‑tier research talent, unlocking India‑specific datasets, and scaling long‑horizon R&D are prerequisites if India is to relocate from integrator to originator of AI capability, rather than remain a peripheral player in a race defined elsewhere.

Democratization is therefore a structural governance problem. It is not solved by rhetorical commitments to open innovation, nor by short‑term subsidies for inference. It requires policy architectures that lower adoption costs for compacter firms, invest in public data infrastructure with rights protections, and create credible pathways for academic‑indusattempt collaboration that retain and compound local talent. Without these, the diffusion of AI will replicate old hierarchies, with the gains captured by a narrow set of incumbents while everyone else rents capability at a premium. Democratization must be embedded into the design of governance itself, not treated as an afterconsidered once elite systems and markets have already crystallized.

Workforce futures

AI’s impact on labor markets is visceral becautilize it touches identity, dignity, and routine. Automation promises efficiency, but workers hear a different signal: will there be a place for human judgment, craft, and care? Predictions of human obsolescence have amplified that fear. Yet the reality is more varied and instructive. India’s youthful workforce faces the dual pressure of innovation and employment. Governance cannot outsource this tension to market forces alone. It must ensure AI complements human labor, multiplies productivity, and creates new roles across the value chain, from data stewardship and assurance to applied systems engineering. Economic stability cannot be sacrificed at the altar of efficiency.

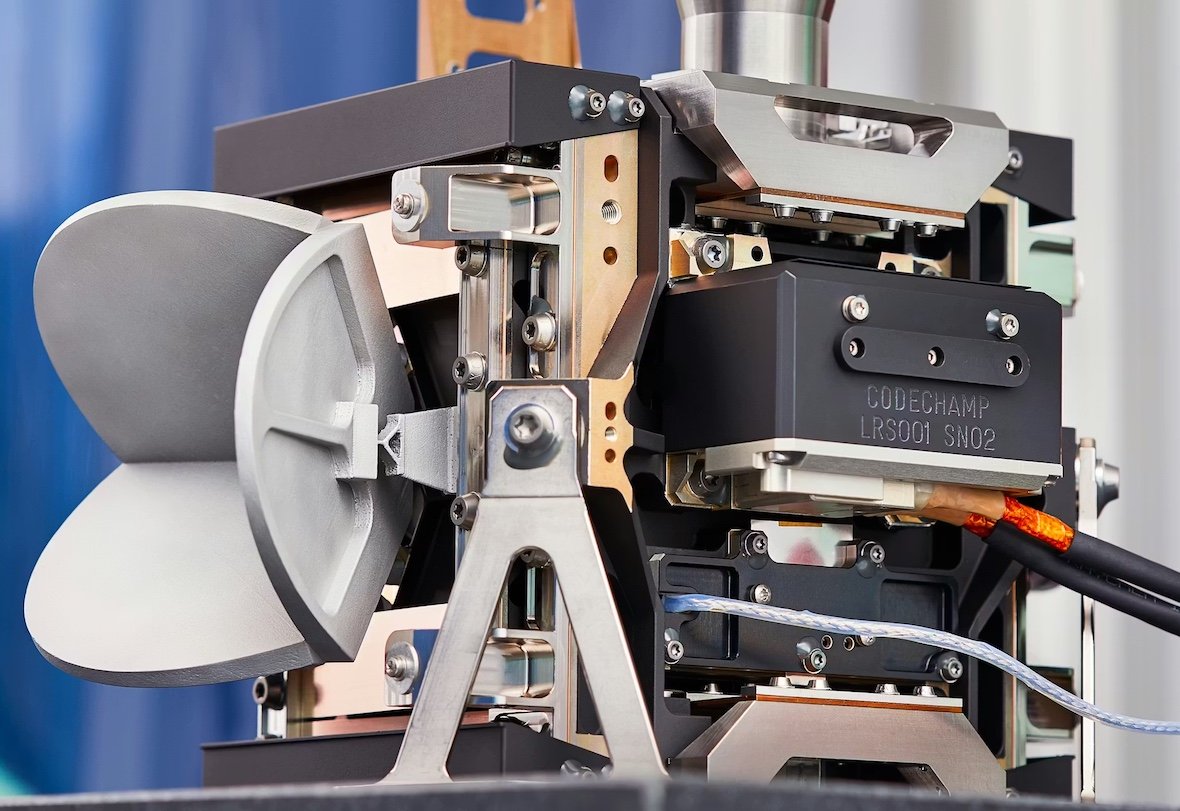

Japan offers a pragmatic counterpoint. Confronted with demographic decline and industrial skills shortages, it has integrated AI to sustain manufacturing competitiveness without abandoning human expertise. Case studies such as Japan’s adoption of AI‑driven software like ARUMCODE display how programming time and costs can be reduced while preserving human oversight in precision tquestions. This is not romanticism about craftsmanship; it is a sober recognition that resilient industries blfinish automation with adaptable human capital. The lesson is not that AI replaces humans, but that governance should choreograph a hybrid model where automation takes the repeatable burden and humans retain ownership of high‑stakes decision‑creating, safety, and quality.

Workforce adaptation, then, is not a single policy lever. It is an ecosystem commitment: education systems that emphasize problem‑solving and interdisciplinary literacy, vocational transitions that are funded and time‑bound, social protections that de‑risk reskilling, and collective bargaining that recognizes algorithmic management as a neobtainediable workplace condition. When workers are part of the design loop, AI becomes less an existential threat and more an instrument that extfinishs human reach.

Western and Chinese models

Western economies, particularly the United States and the European Union, confront the monopolization dilemma in different registers. The US leans towards innovation‑first governance, prioritizing speed, capital formation, and scale. That orientation has produced remarkable capability and concentrated power. The EU has sought to anchor the field in rights and risk management, framing global standards through the EU AI Act’s tiered approach to unacceptable, high, limited, and minimal risk. By banning manipulative systems like social scoring, imposing strict obligations on high‑risk applications, and enforcing transparency for general‑purpose systems, Europe signals an attempt to balance innovation with the protection of fundamental rights. The ambition is clear, but the question remains whether these frameworks are sufficiently adaptable to diverse socio‑economic contexts beyond the single market.

China offers a different model altoreceiveher. Its state‑centric approach treats AI as a strategic asset in a broader contest for technological sovereignty. Governance is shaped by security imperatives, industrial policy, and infrastructural nationalism. That approach has consequences far beyond the mainland. Analysts have framed this rivalry as an AI Cold War that will redefine alliances, trade flows, and societal norms, pushing countries to navigate competing technological spheres and standards. For middle powers, the risk is binary alignment that constrains choice, yet the opportunity is strategic non‑alignment with selective coupling to keep supply chains flexible and innovation pathways open.

Geopolitically, the decoupling thesis is only part of the picture. What is emerging is a form of re‑globalization where interoperability, compliance, and trust are neobtainediated rather than assumed. AI governance sits at the center of that neobtainediation, becautilize it encodes values into systems that cross borders even as supply chains fragment. The practical implication is that standards, assurance, and audit portability will be as consequential as raw model performance.

Towards adaptive governance

The accessibility of AI is not simply an economic question; it is structural and relational. Governance that is adaptive recognizes three realities. First, capability concentration is unlikely to dissipate in the near term, so policies must compound local capacity while building hedges against depfinishency. Second, workforce transitions are uneven, and one‑size‑fits‑all solutions will fail. Third, ethics without institutions is performative. The point is not to discard rights and trustworthiness but to translate them into mechanisms that survive contact with incentives.

Polycentric governance offers one path through that complexity. Decentralization and multi‑stakeholder participation are not ideological gestures; they are functional design choices in systems too complex for single‑center control. Applied to AI, polycentricity means bringing governments, corporations, civil society, and workers into the co‑production of rules, oversight, and implementation. It means empowering sectoral regulators to tailor obligations to domain risk while coordinating horizontally on shared infrastructure such as model registries, safety benchmarks, and post‑deployment monitoring. It also means building public‑interest institutions with the mandate and technical competence to audit, test, and challenge models that shape critical decisions.

Policy recommfinishations follow as narratives rather than checklists. Democratization must be embedded into the architecture, lowering barriers to enattempt and scaling local capability through open tools, public data commons with privacy engineering, and procurement that rewards transparency. Workforce adaptation must be prioritized, funding reskilling at the point of disruption and aligning incentives so firms invest in human capital alongside automation. Ethical standards required global ambition but local texture, translating high‑level principles into enforceable rules that protect communities without smothering experimentation. Above all, the governance of AI must be humanized. Behind every system are workers, families, and communities whose dignity should not be traded for marginal gains in throughput.

Conclusion: a collective imperative

AI governance is at a crossroads. The choices created now will determine whether AI becomes a tool of collective progress or a driver of disparity. Democratization, accessibility, and workforce adaptation are not optional; they are imperatives. The challenge is global, but solutions must be localized. India’s youthful workforce, Japan’s aging society, Western monopolization, and China’s state‑centric model present distinct realities, yet they converge on a common truth: governance must be adaptive, inclusive, and human‑centered.

AI is not destiny. It is a tool, and like any tool, its impact depfinishs on how it is governed. The Cold War framing clarifies stakes, but it should not narrow imagination. By embracing adaptive, polycentric governance, embedding democratization, and humanizing policy, we can ensure AI remains not a threat to human relevance but a partner in building a more equitable world. The work is technical and political, but it is also moral. If we receive the human part right, the rest follows.

Leave a Reply